Research-Based Teaching

Integrating industry-based research into teaching

Since one of the main aims of the UPSKILLS project is to prepare students from language-related study subjects for the job market and several such students will inevitably find jobs in the language industry, the introduction of research projects that are coming from it in upskilled curricula is an important part of our overall vision. In this part of our second intellectual output, we describe the efforts made to integrate industry-based research into our teaching. We present challenges and opportunities from both the perspective of industry and academia, possible formats, the steps we took to implement industry-based research in teaching in the framework of UPSKILLS, and describe successes and challenges we encountered along the way.

Giving students the opportunity to work on a project where industry is involved can be a valuable experience. Many students will find themselves looking for a job outside academia after their studies. Getting a taster of how the industry works during their studies can help them to better prepare for the job market, both in terms of seeing what skills are needed and in terms of knowing what the upsides and downsides of working in a particular industrial setting are, so they avoid future disappointments and choose a job that fits them better. Also, for several students, the experience of working on real-world problems gives a sense of purpose to their university curricula, which may otherwise remain quite abstract.

In the UPSKILLS project, we defined one task whose aim was to explore different formats in which students could get this exposure to the world outside academia during their studies, and to gather experiences that will help lecturers in language-related studies to implement such collaborations between industry and academia. At the initial stages of the project, we gathered information about the consortium and associated partners’ experiences with industry-based teaching, and collected feedback with respect to both our academic and industrial partners’ expectations in relation to the task at hand. Following this, we implemented the most suitable formats in the teaching schedule of three different academic partners, in collaboration with four industry ones.

Against this backdrop, in this report, we first present the challenges and opportunities that industry and academia identify when it comes to incorporating industry-related research projects in higher education curricula. We then turn to discuss some ways in which contacts between industry and academia can be initiated before describing a number of possible formats for integrating industry-based research in tertiary education teaching and identifying their advantages and disadvantages, so as to help lecturers and industry be better prepared for such collaborations. Finally, we present our own experience with implementing industry-based research in our teaching within the framework of UPSKILLS, and additionally survey the experiences of students, academics and industry partners involved.

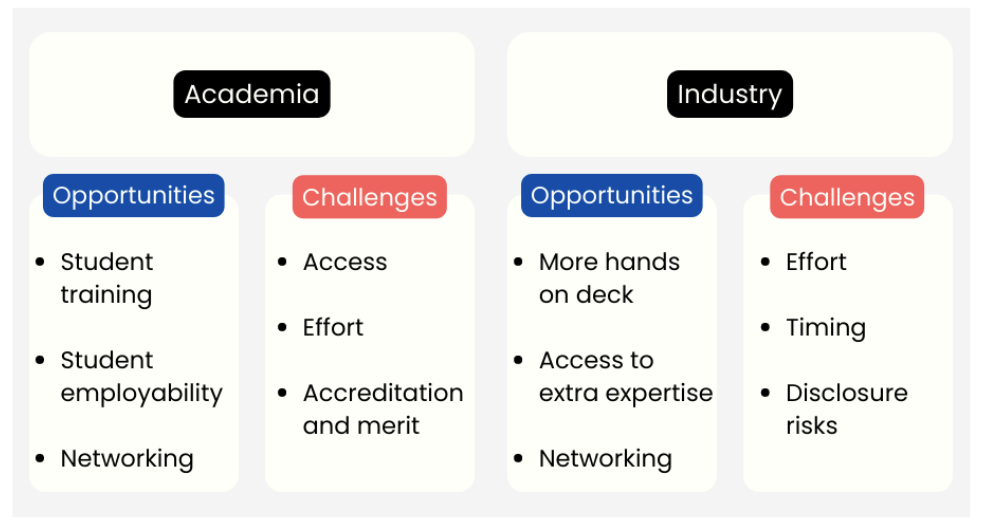

The UPSKILLS consortium comprises eight partner institutions (with academics working in a variety of areas, such as AI, NLP, translation and machine translation, linguistics, etc.), while the UPSKILLS Advisory Board includes three more academic partners as well as six members from the industry. The implementation of this task kickstarted with the gathering of information from the partners and especially the Advisory Board members about their previous experiences with academia-industry collaborations in relation to higher education curricula. On the basis of the feedback received, we identified a number of opportunities and challenges that present themselves when it comes to integrating industry-based research into teaching.

Figure 1. Opportunities and challenges for academia and industry

Academia

Academic partners identified several opportunities for them. By introducing interactions with companies, students get better prepared for the job market, in that they get a taste of what to expect, should they end up working in the industry. At the same time, students can mention this experience in their CVs, which is bound to boost their hiring potential – let alone that they may even end up getting hired by the companies they collaborated with in the future. Also, from a scholarly perspective, working with real data and real-world problems can be particularly rewarding (for students and academics alike), as the research conducted is actually used in a real-life application. Lastly, specifically for academics, creating links with the industry can be readily conducive to further potential collaborations in the future, such as joint involvement in research projects.

Apart from the opportunities mentioned above, academics also mentioned several challenges. For one, there is extra work involved. It takes quite some effort to talk to industry, define a task, and get students ready for it; plus, for some fields, the link to the industry sector might not even be straightforward. The question is whether it is worth the effort. Will the benefits that the students get out of this outweigh the effort needed to establish such a collaboration? Another challenge lies in the very nature of projects. Companies often have different aims that may compromise the student’s aim of academic excellence. They may simply need to get a specific job done, so it is up to the lecturers to make sure that the collaboration involves a sufficient educational component that is linked to the student’s curriculum. In this regard, the question becomes: Are companies willing to try and define an interesting task for the students, or is their main aim simply to obtain some data after a potentially repetitive and tedious task? Ideally, companies should be prepared to give students interesting tasks to work on, but even if that is not the case, the experience may still be a worthwhile experience. After all, it is quite probable that students may find themselves in this situation after they graduate and decide to work in a company, so such an experience may be challenging at the time, but valuable when it comes to future career decisions. At the very least, however, and given the support of their lecturer, the student could still try to make the project more interesting.

Finally, there are some practical concerns. For example, a lecturer who embarks on a collaboration like this will need to decide on a reward for the student’s work. This could be in the form of ECTS credits or a monetary reward, but the former is only possible if the project is linked to a specific unit. Another practical concern is how to get in touch with the industry in the first place. We found that some partners in the UPSKILLS project were already involved in many collaborations with companies, while others were much less so, which could make it challenging for them to approach a prospective industrial partner. At that, however, it is important to note that existing experience on this was not only reported by our partners that work in technical subjects, such as natural language processing (NLP), that thus had easier access to companies, but also by partners in more traditional fields, such as that of translation.

Industry

On top of the fact that through such collaborations, companies might be able to identify new recruits among the students involved, a major opportunity for the industry is the extent to which a relevant setup can allow them to get extra hands to do tasks that may otherwise not get done – or at least not get done on time. Additionally, by involving several students in the same task, a company can get higher-quality data by checking inter-annotator agreements, as is typically the case, for example, for paraphrasing tasks. What is more, through the collaboration with lecturers and students, a company can get expertise on certain topics that it may not have specialists in. Lastly, similar to academia, industry can also benefit from creating links with academia for potential collaborations in the future, as in the case of launching joint research projects.

Along the same lines, some of the main challenges for the industry are similar to the ones that were identified for academics. Companies are often worried about the effort involved in training someone new; let alone a student who is not even a long-term investment for them. Even simply describing a task, preparing the data, and getting students ready to work on it can take up a lot of resources. However, if the industrial partner can maintain a collaboration on the same course in subsequent years, this may well entail less effort and easier planning.

Another challenge is that of timing. Companies often need particular tasks to be completed within particular (and, more often than not tight) deadlines. On the other hand, academia is bound to certain timetables, such as the semester periods. Hence, finding the right time to engage in research collaboration that specifically involves students can be challenging. A potential solution to this issue would be for the industry to find a task that is not urgent, or perhaps not necessary for some immediate project, but simply nice to complete on a more general scale. Another challenge is the risk of disclosure. In this setting, students will often need to work with data or code that is proprietary, so chances are that they will need to sign a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) before they can proceed to do so.

As previously mentioned, depending on the area in which an academic is working, it can be quite challenging to establish contacts with industrial partners. Typically, academics in more technical fields, such as NLP, have more opportunities to get in contact with the industry. For example, lecturers from the Institute of Linguistics and Language Technology at the University of Malta (UM) recounted that they often have companies approaching them for collaborations. For example, on one occasion, they had a visitor from the Directorate General of Translation of the EU Commission, who gave a short presentation of what they do and what problems they face to students in the BSc Language Technology as part of the course Multilingual Language Technology. The students then worked on an assignment based on a task the visitor provided, using data provided by them (on this occasion, a list of medical terms). Eventually, the visitor and her colleagues communicated to the students the results of the systems that they had helped create. Such opportunities may also arise in other contexts, such as that of a conference; on one such occasion, a company (IBM US) approached another partner from UM for a potential collaboration. They ended up supervising an Erasmus Mundus Master in Language and Communication Technologies student jointly for his Master thesis project, which resulted in the production of a patent.

Apart from such opportunistic encounters, internships with companies can be – and often are – part of a curriculum. For instance, the BSc in Human Language Technology at UM has a compulsory internship study-unit, – assessed through a report that students prepare after working in a partner company for 80 hours. Apart from monitoring this process, the lecturers responsible for this unit also maintain contact with and approach new companies that (could) offer internships to students each year. Similarly, even in traditionally less technical fields, such as translation studies, we collected lecturer and company testimonials that recount positive experiences with setting up extended internships, while also noting that this is often a requirement of not only the university curriculum but of many industry representatives too. In this setting, the internships take place with closer tutoring being provided by both academics and industry people, thus also favouring the buttressing of initial superficial contacts.

Another way to establish contact with companies is through a project. For example, a few years back, lecturers from UM submitted a project together with a company to Malta Enterprise. Following a positive experience from both sides, the academic and industrial partners kept in touch through further fruitful collaboration; in fact, as a result of this, the company ended up becoming an associate partner and member of the Advisory Board of UPSKILLS, offering an opportunity for an internship even within this project’s remit. Similar setups are often available even at a more institutional level, such as in the case of translation studies, where the European Masters in Translation Network organises workshops and seminars where industry representatives are invited, thus providing networking opportunities.

Possible formats and implementation

When it comes to the actual implementation of the integration of industry-based research projects, there are several possible formats at the disposal of the academic. One possible format is to define a student project as part of a course. This starts with the lecturer finding a suitable industry partner for a given course. To motivate students to do the task and to allow them to learn as much as possible, the industry partner can be invited to give a short guest lecture first. Then, in collaboration with the industry partner, the lecturer defines an interesting assignment that is relevant for the given course. However, there is also leeway for students to be involved in the process, particularly after they have followed the guest lecture. In this setting, students can be organised in teams to work on the assignment, which apart from being marked for their course, are also passed on to the industry partner for further implementation and/or feedback. Lecturers in the UPSKILLS consortium have good experiences with this model. Of course, this depends primarily on the initiative of the lecturer, but it is bound to be worthwhile for the students who benefit from this experience in their coursework.

Another format to expose students to the industry is through an internship course/programme as part of the curriculum. This format requires more commitment from lecturers but may be more rewarding. Such courses can be offered as compulsory units or electives, in which the lecturers’ responsibility is primarily to stay in touch with industry partners and ensure there is a large enough pool of industry partners to choose from. Typically, students need to be assigned to industry partners and send a CV and motivation letter, so they can practice with this aspect of the job searching process as well. In our experience, in this setting, the best results are obtained when students are assigned to internship roles in pairs or groups (rather than alone). When this route is followed, it is essential to clearly specify the number of hours that the student will have to spend at the company, while taking into account that the allocated ECTS value for this course will also need to account for the time allocated to writing a final report. This final report can, in turn, be used for assessing the student’s work.

Internships can form part of the curriculum but can also be set up independently. Such standalone internships are usually paid and are often the result of some particular task for which a given company might require student expertise. Such internships are usually more focused on the demands of the industry partner and the timeframe set from their end, which means that there is generally less freedom to adapt the work to fit a student’s interests or curriculum. Several UPSKILLS partners noted that this is typical, especially when it comes to annotation work that needs to be completed by a specific deadline – and also pointed out that such internships can be quite popular among students because they involve remuneration.

A last possible way to implement industry-based research into teaching is by means of a joint supervision of a thesis. In this case, a student would normally collaborate with the company, all the while producing a dissertation/thesis related to the role and responsibilities under the joint supervision of the academic and the industrial supervisor. Compared to assignments and internships, this setup requires a considerably strong commitment from all partners. Also, the academic supervisor needs to be prepared to take an active role in safeguarding that the student’s work fulfills the requirements for completing an academic thesis and that the (often practical) goals of the industrial partner is not hampering research work. On this front, one UPSKILLS partner shared an experience where such a joint supervision was challenging, precisely because the student faced challenges in completing the research in an academically robust way. As a result, the supervisor had to step in to safeguard the research component of the student and to lower the expectations of the company.

In the UPSKILLS project, we have had a team working on making a match between companies and lecturers. From the very beginning, we sent out an e-mail and held meetings with all industry-based advisory committee members to gauge their interest in providing student research projects for our partners’ students. We explained to them what the aims of our project were, and asked for possible projects (explaining the type of students we will have, their background, the amount of work they can do etc.). Four of our six associate partners responded positively to our request, agreeing to provide potential project descriptions. Industry partners willing to participate spanned several domains (speech and language technology for the automotive sector, language technology for the financial sector, language technology for the public sector, and machine translation), and provided us with project descriptions with a strong technical component.

During one of the UPSKILLS monthly meetings, we presented the projects and asked our academic partners to volunteer their interest in leading such a collaboration. Lecturers from three different institutions from the UPSKILLS consortium selected three projects. Unfortunately, we could not find a match for all of our industrial partners. One AI tech company in the field of finance proposed projects that relate to several aspects of the NLP pipeline, such as clause splitting, named entity tagging, and sentiment analysis. These were presented to lecturers in the consortium but these topics proved harder to link up to the curriculum of their current cohort of students and were therefore not chosen. Following the matching process, we set up meetings between these lecturers and the corresponding industry partners. After some deliberation, each lecturer decided to either include the proposed project in an existing course, which they would then advertise to students, or advertised the project as a standalone internship. All in all, the following projects were taken on board:

-

- Project 1: Work on building a Maltese lexicon for detecting online hate speech for TextGain, a Belgian text analysis company, with a standalone paid internship status. The project was linked to the European Observatory of Online Hate, which monitors 15 social media platforms for hate speech in all official European languages using Artificial Intelligence. The internship’s aim was to help the company bootstrap hate speech detection for the resource-scarce language of Maltese, as the relevant AI system uses input from human native speakers to learn linguistic patterns indicative of hate speech, and the eventual output was a high-quality Maltese hate speech lexicon of 2300 lexemes. In this case, the student-project match was made by the academic from UM, based on the specifications of the task provided by the company and the quality of earlier student work.

- Project 2: Machine translation evaluation and project management with the status of a standalone compulsory internship with TextShuttle, a machine translation company, for 10 ECTS credits. This was organised under the Translation and Technology curriculum of the MA in Specialised Translation at the University of Bologna. On this occasion, the project at hand was presented to students by the MA coordinator, who asked the students to express their interest in carrying out their internship in this company. After the end of the internship, a person from this company gave a seminar to the 1st year cohort of this same course, and further plans to activate similar internship projects in the future were made, contingent on the company’s resources.

- Project 3: A project on morphological paradigms for Slavic languages in collaboration with Cerence, a multinational AI-for-the-automotive-sector company, as part of a BA course in Slavic linguistics at the Institute of Slavic Studies of the University of Graz. Again, the lecturer went to great lengths to advertise the course with the industrial component to the Institute’s students, but, unfortunately, the course had no takers.

Taking stock

Two out of three projects succeeded in bringing students and companies together, under the moderation of an academic. Βoth projects were completed towards the end of the UPSKILLS project. But did all of this work out well? We present below a snapshot of the feedback we collected from all parties (see also Annex 1, for two full student testimonials).

The feedback was overall very positive. Students enjoyed the experience and found it nice and refreshing to work on a different aspect of language that they had never focused on before. Although they noted that a background in linguistics was not absolutely necessary to complete their projects, they did point out that a better understanding of the way the respective languages worked was an additional valuable asset. One student mentioned that the tasks that they carried out were diverse and each of them was very useful and relevant to their studies, in the sense that they got the opportunity to put into practice and deepen what they were learning at university. They also appreciated working with the team that coordinated the internship and enjoyed the fact that they could work in person at the company for a couple of days. One student, however, also had a suggestion for improvement: to have a practical session before starting the data collection and annotation process for their project.

Our industry partners also mentioned having positive experiences with these industry-based projects. They pointed out that they are always open to collaborating on projects with students, as they bring added value and novel perspectives to their teams. However, they also emphasised that while they appreciate the students’ contribution of intellectual property to the company, they also spend a significant amount of time on the project, often equal to or more than the time invested by the students. Furthermore, they mentioned that they could potentially complete the task more efficiently on their own. All in all, the industry partners thought that it is often hard to think of more research-oriented tasks in the context of short projects that are tied to specific university courses, concluding that the co-supervision of a master’s thesis would typically provide a better framework for projects that are more interesting from a research perspective.

The academics involved in this exercise also gave us their views on how the process unfolded. While recognising the added value of this experience for the students and suggesting that they would go through this process again, they also noted that it is often quite challenging for a course to completely match the specific interests of a company, which can make the task of incorporating a project in a curriculum a bit tricky. Due to this, even though the students do get a great opportunity to contextualise their knowledge in a real-life setting, they inevitably also end up doing tasks that are not closely tied to their course’s content. Even so, our academics did acknowledge that, despite such setbacks, these peripheral tasks that may be not-conducive to extending the students’ knowledge in linguistics and/or languages, still play a pivotal role in helping them develop their soft skills.

Finally, as mentioned above, one of our three selected projects did not attract any students. In an attempt to understand the reasons for this lack of enthusiasm, we gathered feedback from students who were eligible but chose not to register for the course that involved the relevant industry-based research component by means of a survey. Overall, there appear to be two reasons behind this. On the practical side of things, there are sometimes impediments in communicating the information to a wide enough pool of students (notwithstanding, of course, the varying degrees of the students’ own interest in checking what is available and being alert to new opportunities each semester). Due to GDPR restrictions in place at the academic institution, it was not possible to forward the call of interest for the advertised course in a distribution list that goes to all the students, so some students might have missed the advertisement. The students who were supposed to take the relevant course provided various reasons for not choosing it. Some of the reasons included lack of time, lack of interest in research on linguistics, vagueness in the description of the task, and reluctance to work with the industry, which is often considered capitalist. Furthermore, the students expressed their conviction that scientific work should not serve to create products that eventually become some company’s property. Similarly , it was pointed out that a more socially-oriented project, such as one examining cultural bias in different AI tools, would have made the offer more enticing. Finally, some students explicitly noted that they are not interested in working on industry-based projects. Their reasoning is that they believe that such projects would limit their creativity and freedom, and that not even monetary compensation would motivate them to participate.

All in all, our experience with integrating industry-based research into teaching under the auspices of UPSKILLS was positive, but also highlighted certain limitations that such an enterprise may involve. From the feedback we gathered from the relevant parties, it transpired that such projects can be particularly conducive to enhancing the student learning experience, even though the focus of the work may be more on soft skills rather than disciplinary knowledge. In either case, the students involved reported a positive experience because they were able to put their knowledge into practice, all the while getting a chance to collaborate with a team in a real-world work setting. At the same time, both our industrial and academic partners noted that they found the experience worthwhile, even though they sometimes had to operate outside of their comfort zone, by dedicating extra time to guide the students and ensure that both the academic aims and the company’s goals were being achieved.

Finally, we learned that some students can be opposed to working for the industry as a matter of principle, while others may not find some particular task interesting or relevant. A possible way to mitigate this is to ask the pool of students beforehand whether a particular topic would interest them, or ask them about the types of topics they like. Another safety measure would be to make sure that the project is suitable for a large enough cohort of students, to ensure that the collaboration does not fall through. In any case, we are pleased to report that the industry-based research projects that we organised in UPSKILLS had a successful outcome. We are also glad to have provided our students with the opportunity to have a taster of what life after studies could look like for them, if they pursue a career path in the language industry.

We welcome feedback on how to better integrate industry-based research into teaching or on your experiences with doing so.