Research-Based Teaching

Guidelines and Best Practices

The main deliverable of the second intellectual output of UPSKILLS addresses the topic of the research-teaching nexus and provides guidelines for individual lecturers meant to assist them in developing both well-elaborated views on the research-teaching nexus and putting these views into practice through the inclusion of their own ongoing research into ongoing teaching in the form of research-based teaching courses.

This part introduces the topic area and the rationale for these guidelines and best practices, as well as the general structure of research-based courses described in the UPSKILLS best practices. In Section A1, we present the general concepts of research-teaching nexus and research-based teaching, discuss the challenges in implementing research-based teaching and outline how the present guidelines and best practices can be used to overcome these challenges. Section A2 discusses research-based teaching in the broader context of the UPSKILLS project, especially focusing on how research-based teaching can be beneficial to the employability of graduates of language-related programmes while also enabling them to make informed career choices. Section A3 presents topics covered in a typical UPSKILLS RBT course grouped into three topic blocks (Research design, Research infrastructures & techniques and Subject-specific aspects), the rationale behind this grouping, as well as the ideal time distribution across the topic blocks. In Section A4, we provide specific advice regarding the identification of the domain within the lecturer’s area of expertise that can be optimally covered in an RBT course, with special attention for the transferable skills that need to be acquired by the students. Finally, Section A5 addresses what students learn in an RBT course, devoting special attention to general research-related learning outcomes. The learning outcomes are organised in a structure that matches the structure of RBT topics presented in Section A3.

Teaching and research constitute the two core activities in academia. However, these two activities are typically planned, performed and evaluated separately. It, therefore, comes as no surprise that the connection between them, usually discussed in the literature under the rubric of the research-teaching nexus, receives little attention in the reality of most academic institutions (for a notable exception, and a rich collection of experiences and ideas, see Bastiaens, van Tilburg & van Merriënboer 2017).

The near absence of attention for the research-teaching nexus at the institutional level has ramifications for the ways academics see these two activities. Existing research on the research-teaching nexus indicates that academics conceptualise research and teaching separately. In a study of the nexus in humanities, Visser-Wijnveen (2009: 141) found that “academics’ conceptions of the research‐teaching nexus are related to their conceptions of teaching and not to their conceptions of research and knowledge”. Moreover, she found that “the conceptions of research and knowledge are more closely related to each other than to the conception of teaching”. The explanation offered by the author is that the conceptions of research and knowledge come from a different source than those related to teaching. For most academics, conceptions of research and knowledge are formed in the course of their research schooling (presumably during their postgraduate studies), whereas their conceptions related to teaching originate from their earlier experiences as students, as confirmed in studies on beginning teachers (e.g. Feiman‐Nemser & Remillard, 1996).

Addressing the research‐teaching nexus explicitly is desirable at all levels, from individual to team, institutional and national. While higher levels are also crucial, our main goal in these guidelines is to assist individual lecturers in developing both well-elaborated views and putting these views into practice in the research‐teaching nexus. We trust that the most logical and rewarding first step is the inclusion of one’s own ongoing research into ongoing teaching in the form of research-based teaching (henceforth, RBT). While the other direction, the advancement of research based on teaching, should not be neglected (e.g. Giraud & Saulpic 2019), the focus of the UPSKILLS project is on the enhancement of students’ skills in ways that will enhance their employability. For this reason, the present document will concentrate on research-based teaching alone.

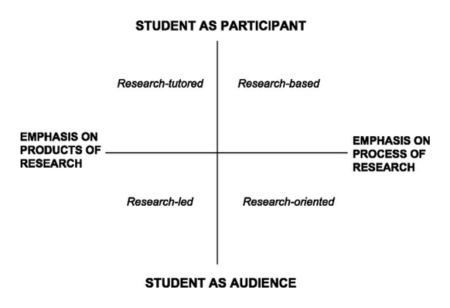

Figure 1. Healey’s (2005, Jenkins et. al 2007) adapted model of the research‐teaching nexus (from Visser‐Wijnveen et al. 2010)

In the model proposed in Healey (2005) and refined in Jenkins et al. (2007), represented in Figure 1 below, research-based teaching is one of the four possible implementations of the research-teaching nexus. Research-based teaching focuses on the process of research rather than on the results of research and involves students as active participants rather than as audience. As such, research-based teaching introduces students to the role of researchers to a higher extent than the other three implementations shown in Figure 1.

The rationale for focusing on research-based teaching in addressing the research-teaching nexus is threefold. First, exposing students to the actual research practices helps them acquire aspects of disciplinary knowledge (including the disciplinary conceptualisations of knowledge and research discussed above) that otherwise remain implicit and unaddressed. As previous research shows, “research awareness is stimulated by a carefully organised close look at their teacher’s research” (Visser-Wijnveen 2009: 141-142). Second, we trust that the everyday research practice of academics involves transferable skills which do not get taught to students during regular courses. Finally, for the lecturers, research-based teaching has the potential of obtaining valid research output from their students but also of discovering teachable aspects of their ongoing research activities that students will find useful or even necessary for their future (academic and non-academic) careers.

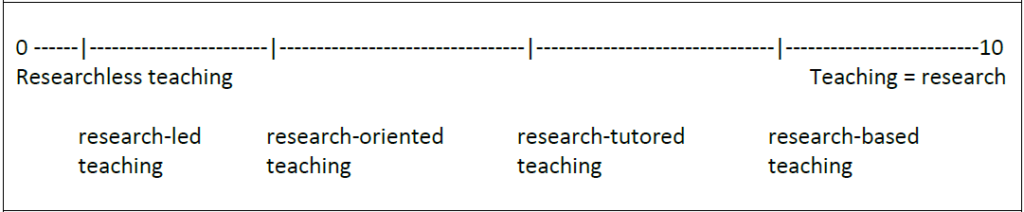

According to Dekker & Wolf (2016), the four manifestations of the research-teaching nexus in Figure 1 are ordered on a scale of the importance of the role of research as in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Dekker & Wolf (2016)’s scale of the research-teaching nexus

A further classification of the research‐teaching nexus, which does not perfectly overlap with the one shown above, is that into five profiles describing what the lecturer does in a course. These are I) teach research results, II) make research known, III) show what it means to be a researcher, IV) help to conduct research, and V) provide research experience (Visser-Wijnveen 2009: 131). Our implementation of research-based teaching involves elements of all profiles but its overlap with profile V) is the greatest, while that with profile I) is the most limited, with all the other profiles falling somewhere in between these two extremes.

In courses with a strong research-based component of the kind that will be discussed in these best-practice guidelines, students are involved in activities of ongoing research projects, using the same research tools and infrastructures that the lecturer uses in their own research. Students can then acquire and actively apply problem-solving and analytical skills to actual data, using approaches implemented in actual research. In some of the scenarios, when the lecturer is involved in this type of research activities, students can also be exposed to industry-based research, which they are likely to encounter in their post-university professional careers. In this setting, industry-based research refers to research that companies conduct as part of their business, rather than with the aim of advancing knowledge, as academics typically do, and comprises a number of tasks that graduates are bound to encounter in their day-to-day workflow when they gain employment in the industry (for more details, see our dedicated report on Integrating Industry-based Research into Teaching).

The concept of research-based teaching is often met with ambivalence by lecturers. Most first experiences with research-based teaching seem to be marked by considerable challenges and frustrations. An important part of these frustrations stems from underestimating how much additional work (but also what kind of additional work) is required in order to set up and run a research-based course. In many cases, research-based teaching is initially perceived as the intersection of two well-known domains (one’s own teaching and one’s own research) and therefore requires minimal additional effort. However, the actual implementation can involve setbacks that are not usually encountered in non-RBT courses.

In the first RBT MA course I taught, the whole concept seemed to be failing already at Class 3. The plan for this class was to discuss how data obtained from a corpus would be further annotated and processed. The students were already working on their specific projects, so I was going to use data from “their” projects as an illustration. From my perspective, the only previous knowledge the students needed was a minimum of Excel skills and some commonsensical notion of how to organise data in a table. What I was discovering at every step is that, as students pointed out, I was using “technical terms without defining them”, something I normally take pride in never doing when I teach. When I asked what these technical terms were, they gave examples like “annotating” and “organising data”, notions which I believed were perfectly transparent for an MA student. We reached an impasse and I wasn’t sure how to proceed. I felt like it was wrong to spend multiple classes introducing such general notions which have nothing to do with linguistics, let alone with the topic of the course. I also had the feeling that I would actually not be teaching them new concepts, but the way we are used to talking about them in the field. I discussed the options with the students. I was open to giving the students a less active role and presenting more research results to them instead, basically making the course research-led. However, the students expressed the wish to follow the original plan, just allowing much more time for additional explanations. I should admit that an important part of my motivation for honouring the students’ wish lay in the fact that we were planning the UPSKILLS project application and I wanted to gather RBT experience. I ended up teaching a whole different course and I was quite satisfied with the results in the end. I realised that I needed to reconsider what I take for granted and plan my RBT courses more flexibly. I decided to include an industry-based research component for a unit called Multilingual Computing, after a visit of a terminologist from the European Commission (EC) to our Institute at the University of Malta (UM). The aim of her visit was among others to strengthen the links between the translation unit at the EC and the UM by working on projects that are beneficial to both. The project the students worked on was concerned with extracting medical terminology available on the IATE Public Database in English and finding a suitable Maltese equivalent by identifying the various Maltese variants which have been used so far in translations of EU legislation. They used computational methods and provided term variants that were then evaluated by the terminologist. I reserved one of the lectures for a talk by a person from the translation unit of the EC with the aim of showing the students a real use case of the things covered in my lectures, after which the students started working on the project. Considering that this was my first experience, it worked pretty well in my view. The terminologist was happy with the results the students provided and could improve the resources for Maltese based on them r. I gave the students clear handles (step-by-step procedure) to get to the results. I think they got an idea of how the methods we were discussing during the lectures could be used in practice. It was quite satisfying to see that the results from their work were actually useful for the terminologist. What I think was wrong in my approach is that I left very little to the initiative of the students. It was not a research experience as such. It was a practical task that was linked to a use case, but it did not give them much opportunity to acquire and actively apply problem-solving and analytical skills. In order for that to happen, I would have needed to spend more time with the students, allowing them to come up with a solution for the problem together. I reserved too little time for that and just gave them a list of steps to follow. I think that this can be a pitfall of industry-based research. The industrial partner involved has expectations and the academic would like to come with useful results. This pressure might lead to the lecturer preferring to give a lot of guidance at the expense of the learning experience for the students.

The challenging aspects of these experiences are arguably traceable to the systematic lack of a well-elaborated view of the research‐teaching nexus, despite clear conceptualisations of research and of teaching. As already previewed above, one of the main goals of these best-practice guidelines is to facilitate the establishment of such a well-elaborated view.

The ambivalent attitude of lecturers towards research-based teaching does not mean that there is no recognition that this form of teaching is useful and necessary. As transpired from the survey we held within the preliminary needs analysis of our project, a bit over 50% of lecturers indicated that they integrate research into teaching, while around 75% indicated that they would be happy to follow dedicated training focusing on this. It is therefore safe to conclude that there is much room for expanding the domain of research-based teaching in the individual repertoires of the lecturers. Also, Visser-Wijnveen (2009: 141-142) found that students enrolled in courses with a strong research component report more learning outcomes on academic disposition and research awareness than their teachers had aimed for in their course designs.

Congruent signals are coming from the industry. The lack of training in research skills, data acquisition and data handling skills were cited by our informants from the industry as one of the major obstacles to integrating linguists into collaborative workflows (Miličević Petrović et al. 2021).

Against the background sketched above, these best-practice guidelines have the goal of giving lecturers a headstart in developing their elaborated view of the research-teaching nexus and developing or improving their own research-based teaching. We complement the existing literature in at least three ways. First, our best-practice guidelines have a disciplinary scope, focusing only on courses in language-related disciplines. Second, they also take into account the employability of graduates of language-related programmes (see next section). Finally, they have a broad testing ground: they are based on experiences from sixteen courses taught by six consortium members.

These best-practice guidelines are especially targeting individual lecturers who are willing to integrate their ongoing research into their teaching. Clearly, they can also be used by research teams, departments etc. to create more variegated RBT courses. While not explicitly addressed, we believe that our best-practice guidelines will also be useful to administrators and policy makers at the university and beyond in articulating their agenda when it comes to research-teaching nexus.

We created these best-practice guidelines in an attempt to establish a general course-design framework that can be easily adapted to most university settings in Europe. However, we are aware that some of the contexts are less welcoming to research-based teaching than others. It is our hope that administrations and policy makers who get in touch with these best-practice guidelines will help take the necessary steps in adopting research-based teaching on a larger scale.

References:

- Bastiaens E., van Tilburg J., van Merriënboer J. (eds.) (2016). Research-Based Learning: Case Studies from Maastricht University. Professional Learning and Development in Schools and Higher Education, vol 15. Cham: Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50993-8

- Dekker, H. & Wolf, W.S. (2016). Re-inventing research-based teaching and learning. Paper presented at the European Forum for Enhanced Collaboration in Teaching of the European University association, Brussels.

- Feiman‐Nemser, S., & Remillard, J. (1996). Perspectives on learning to teach. In F.B. Murray (ed.), The Teacher Educator’s Handbook (pp. 63‐91). San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass.

- Giraud, F. and Saulpic, O. (2019). Research-based teaching or teaching-based research: Analysis of a teaching content elaboration process. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management 16(4), 563-588. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRAM-10-2017-0097

- Healey, M. (2005). Linking research and teaching exploring disciplinary spaces and the role of inquiry-based learning. In R. Barnett (ed.) Reshaping the University: New Relationships between Research, Scholarship and Teaching (pp. 67-78). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Jenkins, A., Healey, M., & Zetter, R. (2007). Linking teaching and research in departments and disciplines. Report. York, UK: The Higher Education Academy.

- Miličević Petrović, Maja, Bernardini, Silvia, Ferraresi, Adriano, Aragrande, Gaia, & Barrón-Cedeño, Alberto. (2021). Language data and project specialist: A new modular profile for graduates in language-related disciplines. UPSKILLS report. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5030929

- Visser-Wijnveen, G. J. (2009). The research-teaching nexus in the humanities: Variations among academics. Phd thesis. Leiden University.

- Visser‐Wijnveen, G. J., Van Driel, J. H., Van der Rijst, R. M., Verloop, N., & Visser, A. (2010). The ideal research‐teaching nexus in the eyes of academics: Building profiles. Higher Education Research & Development 29(2), 195-210. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903532016

The central goal of the UPSKILLS project is to identify skills gaps and mismatches in the curricula of language-related programmes and tackle these skills gaps and mismatches through the development of a new curriculum component and supporting materials to be embedded in existing linguistics and language-related programmes. These measures are intended to enhance students’ employability by providing them with the skills needed to compete for a wider range of positions in the labour market.

We trust that explicit attention to the research‐teaching nexus in general and research-based teaching in particular are beneficial not only to the employability of graduates of language-related programmes but also to their ability to make informed career choices.

One aspect that is often forgotten in the discussions of the employability of graduates is that universities are employers as well and that there is no guarantee that a university will be inclined to hire its own graduates on a research project. At academic institutions where the gap between teaching and research is large and graduates have limited research skills, project leaders may have a tendency to hire graduates from other institutions or even other disciplines. Multiple consortium members can provide anecdotal evidence of this type, where especially graduates of programmes like psychology or computer science seem to have a headstart over graduates of language-related programmes, not because the position requires disciplinary knowledge related to psychology or computer science but because they are more versed in general research skills like data collection, data processing or statistics.

A further negative consequence of a lack of involvement of students in actual ongoing research is that graduates are likely to develop a misguided notion of what research is. In study programs where lecturing and broad yet shallow handbooks predominate in teaching methods, students mistake introductions and overviews for the immediate results of research. This can for instance be observed when students are asked to come up with topics for research for a course paper or a BA or MA thesis, and instead of a research question, they come up with a domain that corresponds to a chapter in a textbook. “I want to investigate secondary predicates’”, or “My plan is to conduct research on the genitive case”. This indicates that students tend to think of research as a purely positivist enterprise in which encyclopedic knowledge is accumulated. This knowledge is then viewed as presentable in a new version of the textbook. Misconceptions of this type may lead the students to avoid a career path in research or research-related pathways or, paradoxically, to strive for one on the false grounds. Experience with real-life academic research is an important antidote to this, enabling students to make informed career choices.

What is true of university-based career paths can be for a good part extended to other career paths. This is because most of the skills identified by the industry as lacking in graduates of language-related programmes in our needs analysis (Miličević Petrović et al. 2021) are essential to research activities performed at their universities and performed by their lecturers. As argued above, these skills are present, but not entirely transferable because there is a lack of attention for the research‐teaching nexus.

While we trust that involvement in actual ongoing research is beneficial as such, we did develop a specific approach largely influenced by our disciplinary focus and the realities of our academic institutions. As already previewed, we are focussing on research-based teaching as the approach which enables the most direct involvement in research practices. A key aspect of our implementation of research-based teaching is the use of a research report as a dominant format of the final deliverable by the student. As will be elaborated below, the research report should have as many characteristics as possible of an ‘actual’ research report (in the sense of being presentable/publishable at an actual academic venue) and it should also be evaluated as such.

As mentioned above, these guidelines are mainly based on our experience with RBT courses. The main instrument of quality assurance was piloting and obtaining feedback from both instructors and students. In the course of the project, sixteen courses were run. We have thus used and will continue to use the feedback from both students and lecturers to reshape the guidelines in order to ensure the broadest possible applicability.

In this section, we present the most general layout of UPSKILLS RBT courses. Many teachers are aware that the involvement of students in specific research projects may carry the risk of being too specific so that the students get a narrow perspective on research, failing to get acquainted with its full width and depth regarding topics, methods and techniques. This is a problem that riddles most involvement of students in internships and student assistantships: students perform tasks that are useful to the project, but without really getting the perspective of the entire research design in which they are participating. In order to avoid this pitfall, our research-based teaching guidelines envision a general introduction to research design as part of all RBT courses. Once the general background is in place, specific research topics can become the testing ground on which analytical and problem-solving skills can grow.

In Table 1, we present the general overview of the topics applicable to any UPSKILLS RBT course.

| Topic block | Topics |

|---|---|

| Research design | General research design: research problems, research questions, hypotheses, predictions, tests, variables, conditions, methods, statistical analysis… |

| Adapting general research design to the specific topic of interest | |

| Adapting the research designto the available research infrastructures | |

| Research reporting | |

| Research infrastructures & techniques | For obtaining literature |

| For obtaining, sharing and managing data | |

| For analysing data | |

| Subject-specific aspects | General question |

| Particular questions, tasks and skills |

Table 1. Overview of topics in an UPSKILLS course

The overview in Table 1 contains three main topic blocks. The order of the topic blocks reflects the order of appearance of the general topic in a majority of UPSKILLS courses (first we discuss the research design, then the infrastructures and techniques and only then do we spend substantial time on the disciplinary issues specific to the course). Also, the relative order of the topics within the topic block is the one shown in Table 1 for a majority of the UPSKILLS courses. However, in most RBT courses, topic blocks will overlap in time, i.e. some specific topics from the first block will be introduced after some of the topics from the second and the third block. (A more detailed overview of topics can be found here). In a detailed course plan, the colour-coding of the different topics can help the lecturer to keep track of the topic blocks and the time dedicated to each of them.

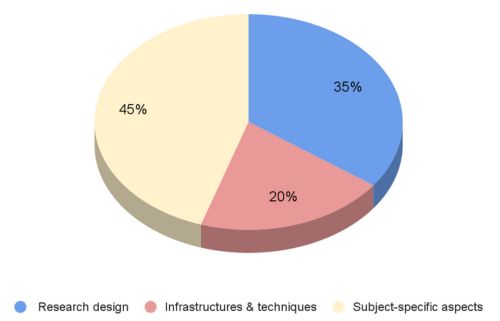

The time dedicated to each of the topic blocks will naturally vary from course to course, but in Figure 3 below we show the ideal distribution of time over the three topic blocks. In the description of the topics below, we also point out the topics that in our experience often turn out to require more time than initially planned, so we recommend planning some extra time for them.

Figure 3. Ideal distribution of time in an UPSKILLS course

We now turn to each of the topic blocks. The topic block Research design contains topics that are common and essential to any research. In a RBT course outline, it should account for a substantial amount of course duration (ideally 35%, no less than 20% of time), since this block contains the most transferable skills inherent to conducting research. As discussed above, in our experience some of these skills may be so self-evident that lecturers may become aware of them only during the course. This is why, especially when the course is taught for the first time, we recommend keeping some room for developing these ‘covert’ skills in the course outline.

As stressed above, it is essential for each RBT course to contain a segment dedicated to General research design. An issue commonly encountered in teaching on this topic is that students have very different levels of previous knowledge and different previous research experience. An additional problem is that it often feels face-threatening to many students to inquire about the very basic aspects, as this is experienced as admitting lacking a clear idea of how research works. One resource which we found useful in shaping the classes dedicated to this topic is the course “Introduction to Research in Linguistics: Theory, Logic, Method”, which was created by some of the consortium members in a previous project. This online course (or parts of it) can be used as preparatory reading followed by a discussion session in which all the basic concepts are covered in order to arrive at a common ground which can be further elaborated in class.

Once an understanding of the general research design is established, we can move on to Adapting general research design to the specific topic of interest, where some initial specific research designs are discussed as applying to the subject matter of the course. Our experience speaks in favour of planning ample time for this topic, as it is one of the topics where lecturers often discover that ways of thinking they take for granted need to be explicated at some length.

One of the most challenging aspects of the RBT MA course that I have taught for my students was identifying and formulating the research problem within the research topic that they were dealing with. Students tended to confuse the research problem (an important gap in the literature that the study aims to fill) with the research question(s) and with the aim(s) of the study. It took a lot of practice and learning by trial and error for the students to learn the distinction between the three concepts and how to formulate the research problem in an adequate way. They didn’t seem to realise at the beginning that it takes more than a sentence to describe the research problem and that using declarative sentences rather than interrogative ones was more suitable for this purpose. What helped the students, apart from my feedback, was providing them with ample examples of formulations of research problems in published research studies and asking them to find such examples themselves. For more details, see the course description in II.III.

While it is useful to consider research designs as if there were no limitations on what can actually be done, once this step is completed, it is important to move on to Adapting the research design to the available research infrastructures. This is a further topic which in our experience usually requires more time than initially expected and should be planned accordingly.

Finally, once an idea of a research design is in place, we can turn to Research reporting. For this aim, we used the general research-report template designed by two UPSKILLS consortium members and presented here. As foreshadowed above, completing this template will lead to the final deliverable of the course, on which also a substantial part of the evaluation will be based. It is therefore instrumental for students to create their own copy of this template and start filling it in as soon as it is introduced to them. As discussed at some length in Section B2 , in adapting the research report template for a particular course, instructors inevitably face a degree of tension between creating a report that closely mirrors the conventions of the discipline (thus resembling a real-world research paper), and one that is as clear and transparent as possible by documenting each step in separate sections. In this case as well, it is helpful to encourage students to ask questions and seek clarification regarding both the disciplinary conventions and the documentation requirements.

I found the course very stimulating, especially because it had some open questions and we had the possibility to work on them for real, with the teacher not only as a moderator but also as a participant. In my learning process, I like to solve quizzes and exercises. However, I believe it is more useful to realise that research is not something that will lead us to a perfect formula, but rather a process that will evolve gradually and still leave us with uncertainty (while hopefully giving us some more knowledge). So, personally, it was very useful to see that the instructor was not just giving us information but also helping us build an attitude towards a discipline.

'Tense in Bosnian / Croatian / Russian' course

The second topic block, Infrastructures & techniques, focuses on the specific tools the students will use in order to implement their research design. This also includes identifying suitable datasets in repositories and using data responsibly. The way the topics in this block are structured is highly dependent on the specific infrastructures and techniques used by the lecturer in their research. However, even in cases where some of the tools are already provided, (e.g. all literature is provided beforehand, so Infrastructures & techniques for obtaining literature could be skipped) we recommend spending some time on each of these topics. For instance, if no literature search is necessary for the specific domain, a minor literature-search assignment can be added on a closely related domain. This theme block also has an important potential when it comes to transferable skills. Working knowledge of tools used in actual research is not only an important asset, but also an important springboard for learning how to use other tools.

It was a leap in understanding the research in linguistics for me to learn to design, prepare and administer online a lexical decision task experiment, and in particular to statistically analyse the data. I believe that the effect would have been even better if I had a better general picture of the theory of lexicon and morphology, because I feel that I do not entirely understand the significance of the results, and of the questions they address. 'Deverbal derivations' course In May 2022 I taught an RBT course at the University of Novi Sad (see II.V for the course description) in which a lot of students’ work took place in a single table on Google Drive, from which various counts and simple statistics were drawn automatically. Two colleagues were sitting in the classes. In December 2022, one of the colleagues told me that they were teaching a course in which, as they said, they implemented my principles and that they were enthusiastic about the results. Once they shared their course outline and materials with me, I realised that the main aspect that they took over was the specific way of using Google sheets with a single big document that many students have simultaneous access to. They did not learn about any of the specific technical possibilities from my course, but just seeing the specific familiar infrastructure in use made them rethink and reorganise their course.

The final topic block, Subject-specific aspects, is used as an umbrella block for all topics which are strictly disciplinary. In all RBT courses a General question can be identified, whose answering typically requires addressing further Particular questions, tasks and skills. This is the domain in which the lecturer is an expert. This block is essential, but it should not cover more than 60% of the entire course outline (ideally 45%). With this in mind, we can now turn to the ways in which an optimal course subject can be selected.

As previewed above, a common feature of all RBT courses is that they are centered around a subject that the lecturer is currently working on or has extensive research experience with. To be sure, this does not exclude course scenarios where the students select the narrower topic for their projects. However, these topics should fall within the area of expertise of the lecturer.

The reason for insisting on the research expertise of the lecturer lies in the fact that, as emphasised in previous chapters, the actual research practices of the lecturer are an important and underexploited resource. While designing and teaching an RBT course, the lecturer identifies research and transferable skills that can be taught to students.

Whereas on the side of the lecturer we recommend sticking to subjects within the area of expertise, on the side of the students no extensive background should be a prerequisite. Here again, the expertise of the lecturer is what guarantees that the necessary background will be provided (e.g., in the form of the best available overview of the state-of-the-art, short presentation, etc.).

In the selection of the course subject, we recommend considering which steps in answering the research question can be performed by the students without extensive assistance by the lecturer and making sure that such steps constitute a majority of the research trajectory. In many cases, there are steps that need to be performed by the lecturer or with extensive help by the lecturer (e.g., the final formulation of the research question, coming up with a data set or performing a complex statistical analysis). In such cases, these steps can be turned into classroom activities, where the students can appreciate what these steps entail and learn how the knowledge lacking at the moment can be acquired in order to perform this step independently.

For several years I taught a BA-level (fourth year) Second Language Acquisition course that was not really RBT, but that involved projects that students did in small groups, on topics of their own choosing (mostly related to the acquisition of specific lexical or grammatical phenomena). The students had regular in-class presentations during which they received feedback from me as well as their fellow students, especially in terms of project feasibility. Overall, things tended to work out quite well, and the students seemed to really enjoy the project activities and seeing themselves as researchers. The two most difficult aspects were rather consistently the formulation of specific research questions within a broader topic and the identification of research variables. E.g., many students wanted to work on the acquisition of English articles or the verbal aspect in Slavic languages, but when asked to narrow down these immense topics, they really struggled and did not actually seem to understand what they were being asked to do. And this was after the same students had already worked, in their third year, on similar projects in a Psycholinguistics course, where the questions were given to them. So my overall impression is that even if RBT is applied, the students should be given an opportunity to work on formulating the questions, even if these will eventually be discarded and new ones imposed by the lecturer.

A further beneficial aspect to be considered when choosing a suitable subject for an RBT course is the possibility of triangulation. If multiple methodological approaches can be applied in addressing the same research question, this is an important asset to be used at different steps of the research trajectory. Groups of students can work using different methods and exchange their experiences and results.

On the one hand, our study programs (Slavic studies) mainly attract students interested in humanities and inclining towards interpretive and other less formal methods. On the other, the general orientation of the UPSKILLS project is to address the demands of industry and general transferable research skills (analytic skills, statistics, use of the infrastructure). In my experience, these two were in a conflict: our students were often put off by the formal, computational, experimental components in the course descriptions. Overall, the same slots in the curriculum had two to three times more students when I taught them in a traditional fashion than when I used them to pilot research-based teaching.

Finally, many research questions can be addressed by applying the same methodology to different samples. In this case, groups of students can work with “their” samples throughout the course and their results can be combined in a single conclusion. While we recommend using the type of data that the lecturer has experience with, the data should not be previously published or analysed (at least using the given methodology). The real-life-like aspect of an RBT course is exactly about the outcome being unknown before the course.

In this section, we address what students learn in an RBT course with special attention to general research-related outcomes. The topics listed in Table 1 map onto learning outcomes which we provide in Table 2.

Topic block

Learning outcomes per topic

Research design

Students will be able to sketch the general research design.

Students will be able to create a suitable research design for the specific topic of interest.

Students will be able to adapt a research designto the available research infrastructures.

Students will be able to report on their performed research in accordance with standards and conventions in the field.

Research infrastructures & techniques

Students will be able to identify and use suitable infrastructures & techniques for obtaining literature

Students will be able to identify and use suitable infrastructures & techniques for obtaining, sharing and managing data

Students will be able to identify and use suitable infrastructures & techniques for analysing data

Subject-specific aspects

Students will be able to address a general subject-specific question

Students will be able to address particular subject-specific questions, carry out particular subject-specific tasks and develop particular subject-specific skills

Table 2. Learning outcomes per topic block in an UPSKILLS course

A more detailed list of specific learning outcomes is available here. As will be discussed in the following section, we suggest using this more detailed list when creating an RBT course. Unsurprisingly, subject-specific learning outcomes (the yellow zone) are defined only in a very general way in this overview because they depend on the specific subject of the course.

The learning outcomes in the first two topic blocks reflect competences necessary in research on which the course was based, ranging from very general research skills to familiarity with specific techniques and infrastructures. Each of these skills has application beyond the immediate academic context in which it was initially presented.

Well-defined learning outcomes naturally connect to evaluation tools. As already mentioned above, we suggest using the research report as the main deliverable by the student, on which an important part of the final grade is based. In our experience, the complete report allows for evaluating the students’ work on all of the course outcomes. However, it does occur that students omit some of the information from the research report necessary for the evaluation. It is therefore commendable to plan at least one round of feedback before the final submission of the research report, so that specific aspects can be further elaborated. We discuss the assessment and evaluation in an UPSKILLS course in further detail in Section B3.

With the necessary groundwork in place, in this part, we lay down specific recommendations for the creation and implementation of an RBT course. Section B1 presents a step-by-step roadmap from the selection of an RBT course subject to designing a preliminary course plan. Section B2 tackles the workflows in an RBT course, the optimal use of the research report in framing and organising the students’ work and the recommendations for writing (research) instructions for students. In Section B3, we address the optimal division between the portions of students’ work on which they only receive feedback and those that contribute to their final grade, as well as the importance of communicating this distinction to the students in order to foster creativity and encourage innovative thinking. Finally, Section B4 focuses on the issues of data reusability, giving the final feedback to students and debriefing them, as well as on the ways of receiving feedback from the students about the RBT course.

We open these guidelines with a quick roadmap to making an RBT course outline. In our experience, the best way to use this roadmap is to open a separate document and start taking notes at each step, moving on to the next step only after completing the previous one. Of course, previous steps can be revised based on insights at later steps.

Based on our experiences with RBT courses we also formulated some DOs (👍) and/or DON’Ts (👎) for each step of the trajectory.

|

Step 1: Having considered the overview in Section A3 and suggestions in Section A4, define a course subject. 👍 Pick a subject that allows spending less than 60% of the time on strictly subject-specific issues. 👍 Pick a subject which is of interest to what you are currently working on or have recently worked on. 👍 Pick a subject you would like to do more research on. |

|

Step 2: Having considered our research-report outline, consider what kind of data you would like the students to work on and what techniques they should apply. 👍 Choose data that can realistically be obtained, processed, analysed and interpreted by students (after instruction that you can reasonably provide). Especially consider the technical skills that the students can be assumed to have. We advise being conservative in these estimations. It is better to be pleasantly surprised than the opposite, which will result in you having to heavily support the students or them failing/feeling demotivated due to initial technical obstacles. 👍 Decide early on if any steps in the process need to be performed by you. For instance, you might decide that you have to provide students with data. This is okay, just make sure such steps are not many and can be presented to the students in a meaningful way. 👎 Working on previously unanalysed data is great, but it is better not to leave students with randomly assigned different and unpredictable datasets for the whole course without building in a possibility of reorganisation, redistribution of work etc. Different datasets may lead to large discrepancies in the workload for different (groups of) students and influence the students’ motivation and course achievement. 👎 It may seem tempting to build in some problems into the data initially presented to the students (e.g., data sets from different populations, wrong annotation, problematic variables) and to make it the students’ task to fix these problems. This type of twist may be a great exercise in courses where the role of students is less active, but it is not very effective in RBT courses, where the students take the role of a collaborator and should have all the information available to the instructor. |

|

Step 3: Using our detailed overview of topics, make an overview of topics you would like to cover in your course. 👍 The blue zone should be at least 20% of the overview. 👍 The yellow zone should be at most 60% of the overview. 👍 When planning the course, leave approximately 20% of the time for “implicit” aspects that you might take for granted at the beginning but actually need to be addressed explicitly. |

|

Step 4: Using our detailed overview of learning outcomes, make an overview of the learning outcomes you would like students to achieve in your course. 👍 Some of the “implicit” aspects that you discovered are likely to turn into outcomes, so don’t make your list too packed. |

|

Step 5: Having the learning outcomes in place, go over and, if necessary, adapt the research-report outline. 👍 Make sure that students get a chance to work individually and in groups, but make the final report individual. Explicitly address how other student’s work should be acknowledged in the report. 👍Ideally, research reports compiled by the students should look like research reports in your discipline. The version that we prepared addresses all the major steps in the process in separate chapters. We found this useful when working with students with little experience with research reporting. When teaching a more advanced group, consider lumping together some of the steps in the report, following the mores in your field. |

|

Congratulations! You have made an RBT course outline! |

RBT courses lend themselves excellently for an outcome-based and goal-oriented organisation. The final deliverable by the students, the research report, is experienced by the students as a tangible result of their efforts, but also as an important milestone in their academic development. As a consequence, students find activities much more meaningful if they view them as a step toward completing their own project report. We therefore encourage introducing the research-report outline at the outset of the course and referencing the specific parts of the outline whenever possible.

It was much easier and less stressful to write my research report using the provided template in several ways. First of all, I would not remember to include all the aspects of the research to be reported without the kind of check-list that the template presents. Second, in the very process of research, there would be more points at which I would not be sure what to do next. And then also, the structure of the report with its structure is informative about the principles and goals of scientific research. 'Language acquisition in Slavic)' course

Since the research report provides the general framework within which all specific activities are situated, we recommend devoting special attention to the adaptation of our research report template to the specific course. As mentioned in Section B1, the version prepared by us has dedicated chapters for all the major steps in the research process. We found this useful when working with students who have little experience with research reporting, as it helps them focus on the content of the report without having to address different steps in the same chapter. When teaching a more advanced course, there is more room for making the research report similar to an actual research paper by lumping together some of the steps in the report, following the mores in the relevant field.

While the research report is a useful final goal, more ‘local’ goals and outcomes also have a role to play in the organisation of the work and motivation of the students. In most RBT courses, both teaching and the actual research activities are divided between homework and in-class activities. In both cases, the purpose of the specific activities and their function in the ‘big picture’ of the course goals may be much less obvious to the students than the lecturer might expect. We therefore recommend starting and closing each activity with an explicit reference to the learning outcomes. For example, if students are supposed to learn to extract a certain type of data from a corpus, and the lecturer provides a brief presentation on how to do that, this outcome should be explicitly mentioned before and after the presentation. At the next step, when the students are extracting data for their own projects, e.g., as part of their homework, this outcome should be referred to before and after this activity. While this may sound overly formal and potentially tedious, it takes less than a minute and our experience is that this helps students to appreciate the type and goal of the activity they are engaging in, as well as to make the most of it. In the absence of explicit tags, some students tend to miss the information on how general the skill is that they are acquiring or disregard the role of this skill in the more general research design.

In most RBT courses, a good part of the steps in the research process is taken by the students as part of their homework. In this case, we recommend formulating the instructions on what needs to be done and how it needs to be documented in the research report. If possible, these instructions should be presented to the students in class and some time (10 to 15 minutes) should be allowed for a Q&A in which any ambiguity is discussed and cleared out of the way. It is actually useful to revise the instructions during the Q&A as necessary, so the same instructions can be reused for another group.

Ideally, the work submitted by students consists of parts of the research report (together with possible accompanying output, such as annotations, lists, descriptive statistics etc.). These are short enough to make it possible to give a sizable amount of feedback in class. In our experience, many comments apply to work submitted by multiple students. Here as well, we recommend keeping track of common misinterpretations of the instructions (e.g., terms which have a specific meaning in the context of the research report). When revising the instructions, the lecturer can consider clearing the confusing formulations out of the way by making the instructions or the rubrics in the research-report outline more explicit.

In an RBT BA course I taught, a seminar on thematic roles, it turned out that the tasks were appropriately demanding, but that there was a problem with the instructions. After a couple of attempts to improve the instructions, I realized that this won’t solve the problem. The simple instructions weren’t sufficiently informative, the detailed ones were too complicated, i.e. included many terms that the students weren’t familiar with and opened room for wrong interpretations. The students asked if it was possible that they begin with the task and send me the materials for feedback, and only then finish the task. This worked very well, so for the rest of the course, the assignments were always split into a pilot part to be submitted by the following class, and the rest for one or two weeks later. The pilot was then always discussed in the next class, the unclarities and misunderstandings were taken care of, and then the students could complete the task properly. This is an option that should always be kept in mind - especially at lower levels of study, and implemented at the first sign of troubles with the instructions.

An important advantage of the students’ work being centered around a single final deliverable, the research report, is that it also allows both the lecturer and the students to keep track of the progress made during the course. For the student, the research report can also serve as a useful indication of the number of completed steps and of the steps that still lie ahead.

Clearly, all research-based courses require the lecturer to provide some necessary background, both on general research-related issues and on subject-specific issues. In our experience, students tend to find it useful if such less active parts of learning are clearly delineated and if the need for them is explicated. One option we recommend is providing the necessary background through a short unit that includes the following parts:

- preparatory reading,

- short presentation by the teacher,

- Q&A

- short (but obligatory) quiz.

While many of our courses have been taught to small groups and, in extreme cases, to single students, we have had some positive experiences with group work in RBT courses. In many courses, a sizable number of steps in the research process can be performed in a group. In this case, the groups are asked to submit a common report in which they also specify the specific contribution of the group members. These reports can then easily be included in the individual research reports.

Quite independently from the amount of work done in groups, we recommend securing a common work space for the entire class both physically and virtually. Furthermore, a cloud or physical repository, where students can share their results, give each other feedback, etc. is a useful addition to any RBT course.

The main bulk of individual supervision in an RBT course takes the form of feedback on intermediate versions of the research report. At least in some academic cultures, it is unusual for students to get a lot of feedback on the piece of work that eventually gets evaluated as the final deliverable of the course, so it is useful to be explicit on how the final grade is calculated and what contributes to it. This is also a way to ensure that the students feel free to try out approaches they are not perfectly confident about in intermediate versions of their research reports.

As previewed above, the main deliverable which also plays a central role in the assessment and evaluation is the final research report. Throughout the course, this research report grows with regular feedback provided both by the lecturer and by peers.

In most RBT courses, there are other essential activities that can be evaluated, e.g., quizzes, group reports, intermediate reports etc. As mentioned above, evaluating intermediate versions of (parts of) the research report carries the inherent risk that the students may not be as creative as in the scenario where they just get feedback on intermediate versions. We therefore recommend including intermediate versions as necessary milestones towards the final research report without evaluating them separately (or evaluating them with a pass/fail mark in systems where this is common).

In Table 3, we give an overview of the general evaluation strategy.

Rubric

Weighing

Participation incl. homework(initiative, forward-thinking, problem solving, critical thinking, organisational skills, time management)

30%

Outputs based on the final research report oral presentation written report

70%

Table 3. General evaluation strategy for RBT courses

The first part of the mark reflects the lecturer’s general impression of the student’s participation in the course. Especially if there is a natural midterm evaluation point, we recommend giving intermediate feedback on this aspect to the students.

For output based on the research report, we suggest using the following evaluation form, which also includes questions to be answered in giving the specific mark.

Take into consideration each of the criteria below that apply to work produced in your course.

👍 Make sure that at least two of the criteria predominantly involve transferable skills (e.g., the students choose and apply appropriate statistical tests, build a database, interview informants) and mark those criteria. Give those criteria a higher weight in the evaluation.

👍 Make sure to keep track of what the students learned in the course (so you don’t expect them to know things you never taught them).

Give the final mark.

CRITERION

QUESTION

GRADE

General

Comprehensibility

Is the output comprehensible for audiences who did not participate in its creation (e.g., can a group of students present their research in a way comprehensible to other students)?

Coherence

Is the output internally coherent (logical flow of ideas, no contradictions, consistent terminology, consistent referencing style, etc.)?

Exploiting conventions

Does the output make use of the conventions typically used in the field (structure, terminology, artwork, a referencing style, etc.)?

Research-related

General understanding of the research design

Does the output reflect a clearly defined and appropriate research design?

Formulation of research questions and hypotheses

Are the research questions and hypotheses clearly formulated?

Formulation of predictions of the null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis

Are the predictions of the null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis clearly defined?

Validity of the employed research design

Does the employed research design adequately address the research question(s)?

Familiarity with the relevant resources, tools and infrastructures presented in class

Does the output reflect sufficient familiarity with the relevant resources, tools and infrastructures presented in class?

Selection of data sources and research techniques

Is the selection of data sources and research techniques sufficiently justified?

Selection of the data analysis method

Is the selection of the data analysis method sufficiently justified?

Inferring theoretical consequences from the specific data analysis results

Does the output reflect the ability to infer broader theoretical consequences from the analysis results?

Table 4. Evaluation for outputs based on the final report in an RBT course

One of the important results of many (ideally all) RBT courses are reusable research results. A way to make sure that these results get properly reused (and the student’s work gets credited) is having the students store their data in a repository as the final course activity. The lecturers who would like to know more about teaching the students how to deposit their dataset in a repository will profit from our dedicated guide on Integrating Research Infrastructures into Teaching and the accompanying UPSKILLS learning content on Moodle, Introduction to Language Data: Standards and Repositories.

Offering feedback on the final research report (in addition to the final mark) means additional work, but students tend to appreciate it. One tool that can be used for this is the evaluation form in Table 3 with answers supported by examples from the report. One advantage of using this tool over writing comments in the report is that positive aspects are elaborated on as well.

We also recommend debriefing the students after the course ends and (if applicable) informing them about the wider academic context of the course, e.g., the UPSKILLS project, further RBT courses etc.

Once the students have received final feedback, it is useful to see how they perceived the course. We created a survey for course evaluation by students which can be used for these purposes. The survey can be further adapted and combined with assessment forms used at the institution where the course was taught.

We welcome feedback from the users of these guidelines. We have created a dedicated survey to be filled in upon completion of a RBT course for which our guidelines were used.

You can also send any type of feedback to Marko Simonović from the University of Graz.